Long before today’s fitness influencers began promoting step challenges and walks for mental health, a sport called pedestrianism captivated America.

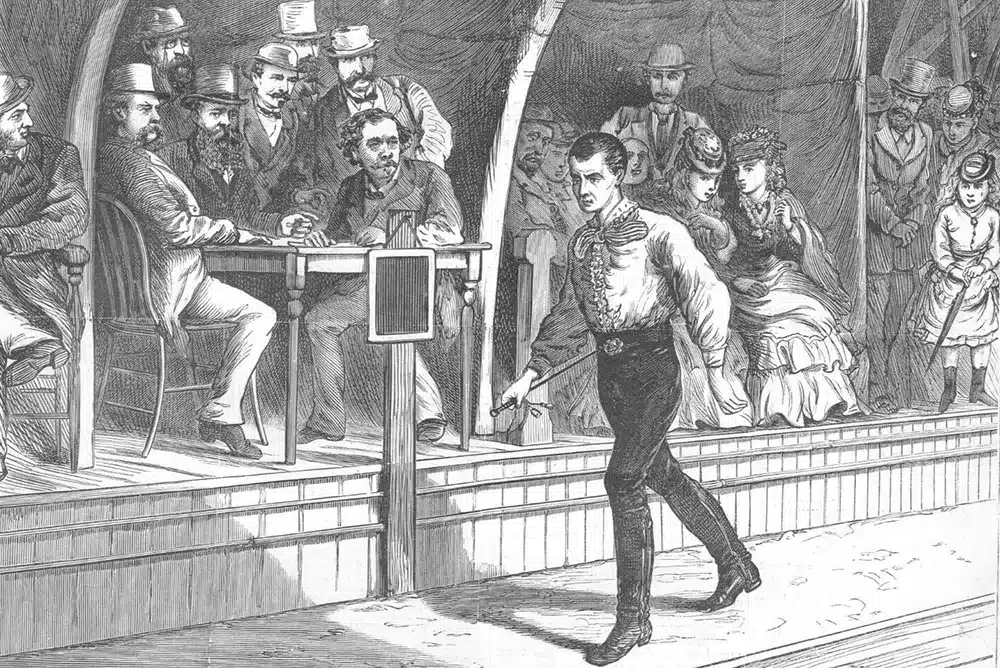

In the 19th century, professional walking was a major spectacle, drawing crowds who paid to watch athletes compete in long-distance walking competitions.

These walkers, known as “peds,” became some of the country’s earliest sports stars, and their feats made walking a form of mass entertainment.

Today, walking is once again having a moment. Social media platforms are filled with influencers who encourage their followers to walk for a variety of reasons, from fitness and mental health to simply enjoying the outdoors. W

alking has become a simple, accessible activity for millions of people looking to stay active. Yet this trend isn’t just about exercise.

Walking groups have sprung up across the country, where hundreds of people gather to walk together each week. The rise of these groups reflects a broader movement that makes walking a social event and a way to connect with others.

Historically, walking has been seen as an ordinary activity, not necessarily linked to athleticism or competition. But in the 1870s and 1880s, professional walking—or pedestrianism—was one of the biggest spectator sports in the U.S. and Britain.

Competitors would walk hundreds of miles, often around tracks or between cities, and large crowds would gather to watch them go the distance. Pedestrianism became so popular that it was known as America’s first mass spectator sport.

One of the most famous walkers of the time was Edward Payson Weston. Weston gained national attention after making a bold bet in 1860.

He wagered that if Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election, he would walk 478 miles from his home in Boston to Washington, D.C., in less than 10 days, just in time for Lincoln’s inauguration.

When Lincoln won, Weston set off on his long journey. He publicized his walk, and as he made his way south, people gathered in towns along the way to catch a glimpse of him.

Despite being delayed by a debt collector and finishing just over four hours late, Weston became a national sensation. Even Lincoln, who was following the story, was so impressed that he offered to pay for Weston’s trip home.

This event launched Weston’s career as a professional walker. After the Civil War, he continued to stage long-distance walking events, and people lined up to buy tickets.

Weston’s walks became a unifying spectacle, with people from all over the country attending to see if he could beat the clock.

At the time, walking wasn’t a popular form of exercise, but Weston and other competitors who emerged during this period helped spread the appeal of pedestrianism.

The sport captured the public’s imagination and grew into a national craze.

Professional walkers weren’t just athletes—they were celebrities. As the sport gained popularity, the “peds” became some of the first mass-market stars in American culture.

They used their fame to promote products, from shoes to trading cards, and even sold advertising space on their clothing during competitions.

In this sense, they were much like today’s fitness influencers, using their platform to monetize their athletic achievements.

The appeal of pedestrianism lay in its simplicity. Walking is something everyone can relate to, and the idea of pushing this everyday activity to its limits intrigued people.

Walkers like Weston made the sport feel personal and accessible, yet extreme at the same time. Audiences connected with the athletes, seeing them as relatable and real, while marveling at their ability to walk incredible distances.

One of Weston’s greatest rivals was Daniel O’Leary, an Irish immigrant who became the “Champion Pedestrian of the World” in 1875 after beating Weston in a six-day race.

O’Leary wasn’t just a competitor; he also mentored other athletes, including Frank Hart, a Haitian immigrant who became one of pedestrianism’s biggest stars.

Hart won the O’Leary Belt in 1880 and earned over $21,000 from the event—an enormous sum at the time, equivalent to hundreds of thousands of dollars today.

Women also played a significant role in pedestrianism. At a time when women’s participation in sports was limited, female walkers, known as “pedestriennes,” broke barriers by competing in long-distance walking events.

One of the most famous was Ada Anderson, an Englishwoman who pushed the limits of endurance sports.

In one event, Anderson completed an astonishing 3,000 quarter-mile walks over the course of 3,000 quarter hours.

Despite societal beliefs that intense physical activity was harmful to women, Anderson and other pedestriennes proved that women were capable of extreme athletic feats.

However, pedestrianism also had a darker side, especially for women. Many female competitors came to the sport out of desperation, seeking to escape poverty or abusive relationships.

The competitions were grueling, and women endured harsh conditions, often facing sabotage from people trying to fix race outcomes.

Still, these women made a lasting impact, showing what female athletes could achieve even in the most challenging circumstances.

Unfortunately, the same unregulated environment that allowed pedestrianism to flourish also led to its downfall. The sport became associated with scandals, including race-fixing and early forms of steroid use.

There was even an extortion attempt that ended in a manager’s suicide. As new sports like bicycle racing emerged in the 1880s, pedestrianism’s popularity waned, and it eventually faded into obscurity.

Despite its decline, pedestrianism left a lasting legacy. It demonstrated that fitness could be accessible to everyone, regardless of background or social class.

It also helped pave the way for modern fitness movements, where walking continues to be promoted as a simple, effective way to stay healthy.

Today, walking influencers on social media have a different approach than the professional walkers of the past.

They focus on promoting fitness in a way that’s inclusive and empowering, especially for people who may not have felt welcome in traditional fitness spaces.

For those who want to embrace walking but don’t want to commit to the 10,000-step goal, there’s an easy solution: walk as much as you enjoy.

Even in the 1870s, advice on walking was simple. As the New York Times suggested back then, walking for as long as you like is enough to make you “healthier and happier.”